Even though Abraham Lincoln never visited the Nebraska Territory and died before Nebraska statehood, he had a very large influence on our state.

The Civil War

The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 may have been the single most significant event leading to the Civil War. In that year, the federal government passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, and a large area of land of the Nebraska Territory became available for settlement. Not everyone was happy with the Kansas-Nebraska proposal. Southerners feared it would lead to a territory filled with anti-slavery settlers. The anti-slave people worried that at least a part of the area would be filled with pro-slave settlers. The passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act would lead to violence between pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers in Kansas (“Bleeding Kansas”). Slavery was quite likely to be outlawed in Nebraska, where cotton doesn’t grow well. The situation in Kansas was entirely different, where the land was similar to Missouri’s, which was a slave state.

The presidential election of 1860 proved to be the pivotal point leading to the Civil War. The North could never accept a President who planned to protect or extend slavery. The South would never accept a President who refused to do so. The nomination of candidates and the election of a northern President in 1860 were among the most divisive events in the history of this nation. Abraham Lincoln was President, and within weeks, seven states left the Union to form the Confederate States of America.

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina seceded from the Union. Five days later, sixty-eight federal troops stationed in Charleston, South Carolina, withdrew to Fort Sumter, an island in Charleston Harbor. The North considered the fort to be the property of the United States government. The people of South Carolina believed it belonged to the new Confederacy. Four months later, the first engagement of the Civil War took place on this disputed soil and the Civil War had begun.

President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to help fight in this rebellion. The call was heard all across the country, even in the new territory of Nebraska. In June and July, 1861, companies were raised throughout the territory and surrounding states. The First Nebraska regiment was led by John Thayer and fought in the famous battles of Fort Donelson and Shiloh along with other minor engagements in Missouri and Arkansas. In October 1863, the regiment was changed from infantry to cavalry, and was transferred to the frontier to battle the Plains Indians. The regiment was finally mustered out of service in 1866. By war’s end, the Territory of Nebraska had offered more than one third of her eligible male population to the war, a ratio even greater than the Union’s most populous states.

The Homestead Act

In the 1830s, the federal government had declared the land that was to become Nebraska as Indian country ”” a place where Native Americans could live as independent nations. But with passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, the government went back on that promise and opened the land to settlement.

To encourage this settlement throughout the West, the U.S. Congress passed the Homestead Act and President Lincoln pushed for the building of a railroad across the country. The Homestead Act of 1862 gave 160 acres of public land to any head of household who lived on the land five years to encourage construction. They offered this land for sale to immigrants at low cost.

Daniel Freeman may have been the first homesteader to file a claim under the new law. Freeman was a soldier in the Union Army on secret duty at Fort Leavenworth in Kansas. He may have been a spy. It is known that for some time he had his eye on a piece of land near Cub Creek in Southeastern Nebraska near Beatrice. Freeman knew that the Act was going to go into effect on January 1, 1863. According to the stories his family passed down, Freeman had to be back in Fort Leavenworth on January 2. The story has it, he persuaded the registrar of the land office in Brownville to open up shortly after midnight on January 1, making Freeman the first homesteader in the entire nation.

The Trans-continental Railroad

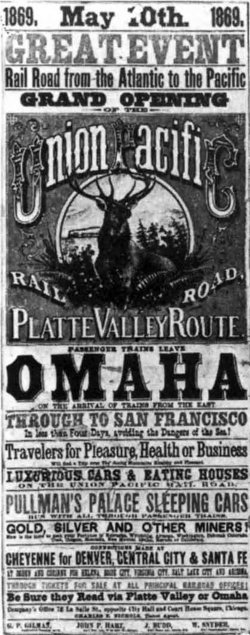

At the height of that war, President Abraham Lincoln sought a way to connect and secure the great expanse of our nation, to entirely unite it from the East Coast to the West Coast. Many leaders felt that the time for such a massive undertaking was not in the middle of an expensive Civil War. But the president was determined. At the same convention where Lincoln was nominated, the Republicans pledged to stop the spread of slavery, to establish daily mail service and to build a transcontinental railroad. In Lincoln’s mind, the railroad was part of the Civil War effort.

The Central Pacific would start at the Pacific and head east while the Union Pacific would start in the middle of the country, the beginning of the frontier at the time, and head west. Even before he became president, Lincoln was very interested in a Pacific route to the West Coast. On a visit to Iowa in 1859, he met with Grenville Dodge, who would one day become Union Pacific’s chief engineer. Lincoln remembered Dodge’s expertise and summoned the engineer to Washington in 1863 to discuss a starting point for the Union Pacific. Dodge was very determined that the railroad must follow the Platte Valley and begin at Omaha-Council Bluffs.

On November 17, Lincoln issued an executive order setting the railroad’s eastern terminus exactly where Dodge had advised. Union Pacific broke ground in Omaha in December 1863. Unfortunately, due to many delays, the first rails wouldn’t be laid until July 1865, three months after the president’s death.

Approximately sixteen percent of Nebraska’s total land mass was given to various railroad companies, either by the federal government or by the state. Along the lines of the state’s two major railroads, the Union Pacific and the Burlington, every other square mile of land (called a “section”) went to the railroads. This checkerboard of land extended back twenty miles on both sides of the track. The railroads owned a total of twenty sections of land for each mile of road they constructed through Nebraska.

The Morrill Act

The Morrill Act was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on July 2, 1862. It was written and sponsored by Vermont Congressman Justin Morrill, and it provided each state with 30,000 acres of Federal land for each member in their Congressional delegation. The land was then sold by the states and the money used to fund public colleges that focused on agriculture and the mechanical arts. Sixty-nine colleges were funded by these land grants, including The University of Nebraska.

Morrill Hall, on the University of Nebraska campus, was named after Congressman Morrill. It houses the University of Nebraska State Museum, the region’s premier natural-history museum. The building is also called Elephant Hall because of its world-class collection of fossil elephants.

Lead Photo: Abraham Lincoln, 16th president of the United States.