Otoe-Missouria Tribe

Four Hundred Years of History

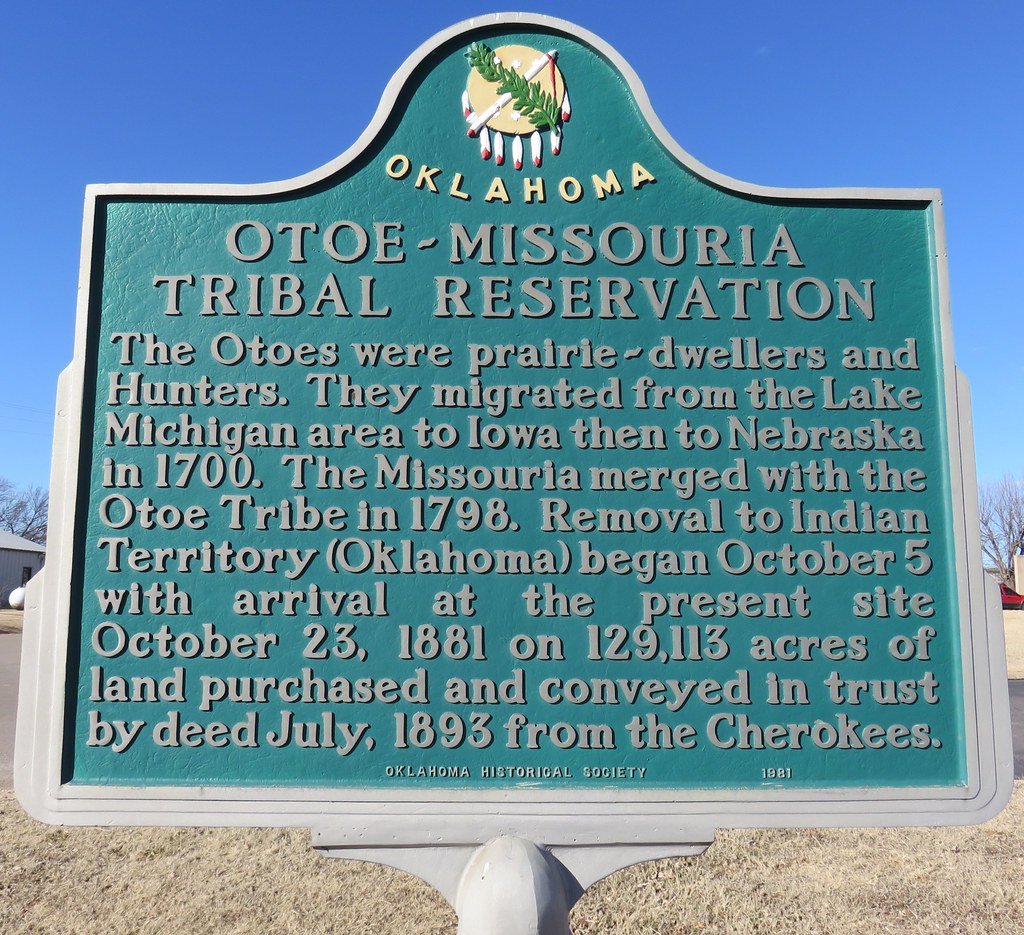

Red Rock, Okla.–At one time, the Otoes and Missourias, along with the Winnebago and Iowa Tribes, were once part of a single tribe that lived in the Great Lakes Region of the United States. In the 16th century the tribes separated from each other and migrated west and south although they still lived near each other in the lower Missouri River Valley.

The Otoes also call themselves Jiwere (jee-WEH-ray) and the Missourias, who call themselves Nutachi (noo-TAH-chi), were related to each other in language and customs, but they were still two distinct people.

The state of Nebraska gets its name from the Otoe-Missourias. It is from two Otoe-Missouria words “Ni Brathge” (nee BRAHTH-gay) which means “water flat”. This name came from the Platte River which flows through the state and at some places moves so slowly and calmly that it is flat.

The state of Missouri and the Missouri River are both named after the Missouria Tribe, which once lived in the region and controlled traffic and trade along the Missouri River and its tributaries. Trade was a vital part of Otoe and Missouria life for centuries. They traded with the Spanish, French, English and Americans for various goods. All of these nations courted the Otoes and Missourias for exclusive trading agreements.

European Contact

In the summer of 1804, the Otoe and Missouria were the first tribes to hold council with Lewis and Clark in their official role as representatives of President Jefferson. The captains presented to the chiefs a document that offered peace while at the same time established the sovereignty of the United States over the tribe.

Unfortunately, contact with Europeans also brought new diseases. Smallpox decimated both tribes and weakened their hold on the region. The Missouria Tribe lost many people to disease and warfare with other tribes killed many of the healthy warriors. In the late 1700s, with few people remaining, the Missourias went to live with their relatives the Otoes.

The Otoe-Missourias were predominately hunter-gatherers. They did grow and harvest corn, beans and squash, but this mostly subsistence farming was intended to supplement the bison and other game that made up the majority of the Otoe-Missouria diet. As was their tradition, the tribes would migrate to follow the buffalo, but they stayed in a general area of Nebraska, Iowa, Missouria and Kansas.

The traditional lands of the Otoe-Missouria people were desirable farming lands to the settlers from the east. As more and more settlers came onto Otoe-Missouria land, the tribal people fought to protect it. Although a small tribe, the Otoe-Missourias bravely fought any who attacked them including the white settlers who had essentially squatted on the tribe’s land. This created a conflict for the United States government and they took action to protect settlers. In 1855 the Otoe-Missouria people were confined by the United States government to a reservation on the Big Blue River in southeast Nebraska.

Displacement and Division

Life on the Big Blue Reservation was hard. The tribe was not allowed to hunt for buffalo. The government encouraged a shift from a migratory lifestyle to an agrarian one without consideration of long established tradition or social structure. For years the tribe watched as acre after acre of their land was sold off by the government to non-Indians. They suffered as treaties were broken and food, medicine, livestock and basic essentials were not delivered as promised. Sickness was rampant, children starved and the mortality rate climbed higher year after year.

Under these conditions a new treaty was “negotiated” in February 1869. The treaty set forth that part of the reservation would be sold to railroad lines for right-of-way and that 92,000 acres would be surveyed and appraised for sale. It also stated that a delegation would be sent to Indian Territory (Oklahoma) to explore a new settlement.

Tribal reaction concerning the treaty was decidedly mixed. Part of the people considered removal to be a better alternative than staying on the Big Blue Reservation. Others felt that the tribe should cling to the land regardless of the hardships. The rift would widen and eventually split the tribe.

The tribe divided into two main "groups” the Coyote Band and the Quaker Band. These bands were based on ideology, not clan or birth. The Coyote Band favored immediate removal to Indian Territory. The Quaker Band favored staying on the Big Blue Reservation. After years of suffering under the Office of Indian Affairs, the Coyote Band consisting of some 160 Otoe-Missouria people, escaped the Big Blue reservation for Indian Territory.

For the remaining tribal members conditions worsened. They petitioned the government to remove the entire tribe to Indian Territory in hopes of a better life. On October 5, 1881 a procession of 320 Otoe-Missouria left Nebraska for a new reservation in Indian Territory purchased with the funds from the sale of the remaining lands of the Big Blue Reservation. The assemblage walked for eighteen days and arrived at the new agency on October 23, 1881. The Coyote Band rejoined the tribe at the Red Rock site in 1890.

Once on the reservation, Otoe and Missouria children were taken away from their parents and sent to government boarding schools to be “civilized”. The children had to learn English. Tribal elders remember being punished for speaking their native language at school. The stigma of speaking the traditional language passed into the home. Some tribal members did not teach their children their language because they did not want them to be punished in school or because they thought it would be better for them to learn “white ways”.

Because the language and traditions were discouraged by the government, much of the language has been lost. Today the tribe is struggling to maintain what knowledge of the language still exists. Some of the information gathered by the tribe regarding the language was document by non-Indians, missionaries and government agents.

In 1834, a missionary named Reverend Moses Merrill created a system of writing the Otoe language. He published a book of Otoe church hymns called Wdtwhtl Wdwdklha Tva Eva Wdhonetl. The title of the book translates to “Otoe book their song sacred”. This book is considered to be the first book ever published in Nebraska.

Otoe-Missouria land was again taken from the tribe in 1887 when the U.S. government passed the Dawes Act. The act provided for the distribution of tribally held lands in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) into individually-owned parcels. This broke up the Otoe-Missouria reservation and opened land deemed as “surplus” to settlement by non-Indians and development by railroads.

Present Day

Today most of the more than 3,100 tribal members still live in the state of Oklahoma, but there are members who live throughout the United States including New Jersey, California, Hawaii and Alaska. The tribe is still one of the smaller tribes in Oklahoma, but lead by a progressive Tribal Council, they have parlayed their gaming revenue into long-term investment in other sustainable industries including retail ventures, loan companies, natural resource development, hospitality, entertainment and several other projects still in development. Tribal members perpetuate tribal traditions with feasts, dances, an annual powwow and song leaders continue lineage, clan and tribal ties. If you would like to learn more about the Otoe-Missouria Tribe please log on to www.omtribe.org or call 580-723-4466 ext 217.